Touching the Wild Read online

Copyright © 2014 Joe Hutto

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected]

www.skyhorsepublishing.com

ISBN: 978-1-62636-213-0

eISBN: 978-1-62873-553-6

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Photos on pages 21, 22, 34, 56, 58, 66, 74, 76, 78, 82, 95, 97, 98, 104, 151, 155, 165, 167, 214, 232, 252, 268, 290, 292, and 295 by Leslye Hutto. All other photos by Joe Hutto, unless otherwise credited.

Printed in China

Acknowledgments/References

This book represents, not only a lifetime of work, but a perpetual collaboration involving many disciplines, influential educators, mentors, and those inspirational personalities, both academic and personal, who have contributed to my vision of the natural world. Regretfully, they are too numerous to mention all and I could surely write volumes on every one.

A few of my early personal influences include: Ornithologist Herb Stoddard, botanist Robert K. Godfrey, wildlife biologist Lovett Williams, and paleontologist Stanley J. Olsen, all of whom taught me that the most rigorous science was perhaps the most fun a human being can have, when the wonder and curiosity of a child can be sustained throughout a lifetime.

Among so many scholarly and philosophical contributors I must mention the works of Aldo Leopold, Olas Murie, Loren Eiseley, Nikolaas Tinbergen, George B. Schaller, Jane Goodall, Edward O. Wilson, Derek Bickerton, Arthur Zajonc, Konrad Lorenz, and Henry Thoreau. Their collective genius and influence cause me to wonder if I have ever had an original thought in my life.

Contributors to our understanding of the mule deer of the American West are many and I must name but a few that have had more direct bearing on this study. It is impossible to consider the mule deer without some mention of the standard reference: Mule and Black-tailed Deer of North America—a research anthology involving many important contributors, compiled and edited by Olof C. Wallmo. In addition, there are many more recent studies that have been referenced directly in this book that include the stellar work of: Werner T. Flueck, Susan Lingle, Hall Sawyer, Fred Lindzey, and Doug McWhirter.

Further, it is difficult to say anything of significance about the North American mule deer without mentioning evolutionary biologist and professor Emeritus of the University of Calgary, Valerius Geist. It was his influential advice and encouragement that once suggested that there was valuable work to be done and it was he who in large part inspired me to make a commitment to this extraordinary animal.

I will always be indebted to a team of supporters who have become more like family members than employers and colleagues. PBS Nature series Executive Producer Fred Kaufman along with Bill Murphy, Janet Hess, Janice Young, Laura Metzger Lynch, and Jayne Jun—WNET, New York, all shared a vision for the potential of this project. This vision was realized and brought to light in the truest sense by Passion Pictures based in London England. Producer David Allen and assistant Gaby Bastyra, along with a team of technical people that must be one of the most gifted assemblages of profoundly inspired human beings to have ever come together with a common purpose. The celebrated cinematographer Mark Smith along with filmmakers Dawson Dunning and Sammy Tedder, made living and working in the wilderness, often under the most difficult circumstances, an honor, a privilege, and a pleasure of the highest order.

I am indebted to State wildlife agencies all over the West including: Colorado, Nevada, South Dakota, Idaho, Montana, and, of course, Wyoming. Their research and management data has been crucial and their kindness and encouragement has been humbling. I wish there was a better means to convey to the general public how fortunate we are to have so many enlightened, gifted and dedicated people, so tirelessly intent on making a difference and doing the right thing. It is truly inspirational.

Thanks to Skyhorse Publishing and especially to my most talented and visionary editor, Lilly Golden, for whom, after so many years and so many projects, my respect, affection, and gratitude has become complete.

No small attribution is owed to my friend, partner, and wife Leslye. My love and gratitude is immeasurable, as this journey has also been hers—every step of the way.

Table of Contents

Preface

Part I: Some Interesting Mule Deer I Have Known

1. In the Beginning

2. And Along Came Rayme

3. An Inflorescence of Mule Deer

4. Peep’s Diary

5. Anne of a Thousand Days

6. Living Among the Mule Deer

7. And Then There Was Possum

8. The Babe

9. Making a Case for Mule Deer Miracles

10. Buck Friends

Part II: The Essential Mule Deer

11. Mule Deer versus White-Tailed Deer

12. The Essential Mule Deer

13. High Society: Altruistic Does and Beneficent Bucks

14. The World as Perceived by a Mule Deer

Part III: The Mule Deer in Crisis

15. The Predators

16. The Trouble with Mule Deer

17. Updates on Old Friends

18. Provisions of Consciousness

Epilogue

Preface

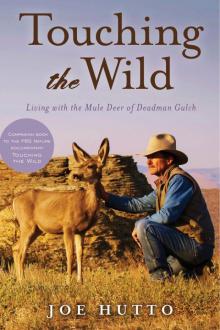

I have lived with a large herd of mule deer in the mountains of the Wind River Range in Wyoming every day for the past seven years. How, you may ask, can a person do such a thing, and why would he choose to do it? My response would be, how could you not? Given the opportunity, how could a person resist such a life? You can call it biology or, better yet, ethology, or, perhaps more generally, natural science. But a more accurate description of this particular study would be the expression of some irresistible necessity to find sanctuary in the proximity of wild things. Necessity would be the key word in this case. I am compelled to seek out and explore the lives of other creatures—not to know simply what these animals are biologically but, more interestingly, to know who they are and how their biological affiliation, as a member of a species, instructs them as individuals. Ironically, it is through understanding individuals that knowledge of a species can truly be revealed. Although there can be strictly quantitative approaches, ethology—the study of animal behavior in a natural setting—is by definition a rather subjective undertaking. But divining the “who” of an animal can be an unapologetic departure from hard science and an adventure into a qualitative behavioral realm. One of my hopes is to maintain that balance along a challenging narrow divide between science and sentiment. My other objective is to be the voice for this extraordinary animal, which at this time is in need of a powerful and persuasive ally—an advocate—and that advocacy will come only from the various people that by way of different but convergent paths come to know and love the mule deer. Ultimately, the North American mule deer is in trouble on a bewildering array of fronts. And if we do not take any action, we may watch this species fade into oblivion.

We need not fear the emotional ties that will inevitably develop as we draw near to some thoughtful creature that is, without question, returning our gaze—an undeniable participant in an inquiry that clearly has become mutual. Sentiment born of the simple and logical empathic recognition that

as living things we all share certain distinct similarities can be a lucid window into the life of an animal, providing the means to keenly observe some subtle elegance and beauty that may otherwise be overlooked. Empathy provides us with the vision to gain understanding, not through some superior anthropomorphism, but through our objective biological membership as analogous living things.

The practice of ethology may be better suited for the obsessive personality. Studying animals in their natural environments can involve slogging through aquatic habitat, trudging up mountains, scaling tall trees, suffering in steaming heat with ravaging insects, or enduring bitter cold. You are hungry, you are cold, you have not slept, and you don’t care. Not because your obsession is pathological or you have an inherent fondness for suffering, but because the level of entertainment is so high—the intensity of discovery so rewarding and undeniably fun—that your discomfort becomes irrelevant. You wouldn’t trade the privilege of your exploration for anything on Earth. And then, perhaps—just perhaps, at last—you may become aware that your subject matter and the flood of knowledge being revealed could actually be important.

Since I was a child, I’ve been drawn to studying animals. When I was ten, I captured and raised every newborn creature I could get my hands on, from crows to coyotes. Eventually, in college, I had the opportunity to work with bears, big cats, and even baboons and mandrels. It was also during these years that I worked with many species of cervids—deer and elk—and immediately became intrigued with the many interesting aspects of their social behavior. The more complex animal societies such as those of crows, baboons, and various herd animals including bison and deer captured my imagination and seemed to offer the greatest challenges—and opportunities. Even though I had been involved in land and wildlife management for decades with an emphasis on game animals, I later became drawn to many of these same popular species, not because they were important game animals, and certainly not because I was being handsomely paid, but because these animals were in fact prey species that are characterized by larger, more dynamic populations, and thus often display elaborate social organization. Growing up in a waterfowl hunting culture in the rich and diverse wetlands of northern Florida, I had always had a bit of an obsession with ducks and geese.

One of my first attempts to finally conduct a fully rigorous ethology using the phenomenon of imprinting involved a newly hatched nest of orphaned wood ducks. Imprinting is simply the means by which a newborn animal comes to identify its parent and, perhaps, to some extent, its affiliation as a member of a species. I lived with these birds in the water of a bay swamp as their parent every day from the moment they hatched until the survivors were adults at about six months of age. The experience was a life-altering revelation, as I gained entry into the life of the wood duck, revealing a world with nuances and complexities that were previously beyond my comprehension. These creatures proved to be infinitely—outrageously—more intelligent and interesting than I could have imagined. I was not only struck by the complete and fully articulated instruction inherent in their genome, but also amazed to understand the depth of their ability to reason through the labyrinth of their universe with true problem-solving intelligence. That was the intimate experience that made me realize the untapped potential for discovery among many wild species, and that this was a largely unexplored realm—wide open with possibilities that seemed to shake up my world. The wood duck project demonstrated that there was abundant and fertile new ground to be broken, and that this not only was serious business, but could even be considered important work.

Years later, after in-depth involvements with gray foxes, crows, and several birds of prey, I repeated a similar but even more intense imprinting study involving wild turkeys: I incubated, hatched, and lived with a large family of twenty-four individuals for more than two years in a remote “wilderness” setting, largely isolated from human contact. The project resulted in the book Illumination in the Flatwoods, which, to my great surprise, was well received, by many casual students of natural history and scientists alike. Astonishingly, an Emmy award–winning documentary film, My Life as a Turkey, based on the book followed and proved beyond a doubt that not only are people interested in the seemingly obscure lives of wild creatures—they are hungry to know how other creatures envision the world. And it has become clear that some people find emotional or possibly even spiritual consolation in the notion that humans are fully capable of establishing complex and meaningful relationships with other independent living things in ways that do not involve dominion or control.

Author with young wood duck, 1978.

The author with Stretch, one of the turkeys from his 1995 experiment involving imprinting wild turkeys.

Then, a few years later, I found myself living under rather strange circumstances, among another society of obscure animals, as a field biologist on the Wyoming Whiskey Mountain bighorn sheep study, beginning in 2001. This time I found myself living on a remote mountain in the Wind River Range, at twelve thousand feet, far above timberline, embedded with a summering herd of Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep. I lived alone in the company of these rare animals for months at a time without seeing another human in an effort to uncover what mysterious circumstances were limiting lamb survival. As in previous studies, a society of wild creatures seemed to become my own social environment—and, to some extent, my own family. My involvement with some of these individuals lasted for years, and included successive generations of young with individual faces and personalities that also came to identify me as a safe and persistent feature in their unique landscape. My affection for all bighorn sheep—and of course for certain individuals—became a powerful and very personal force in my life.

Almost immediately following my involvement with the bighorn sheep study, I found myself once again living among another society of creatures that has captivated my time, attention, admiration, and affection, to the exclusion of most everything else. And so, after spending another seven years of my life within the society and ecology of another animal, it could be said that my human perspective has been altered in some way, and that my identification with my own species has been clouded.

My goal with the mule deer study was to observe behavior in a light that is brighter than that offered by our own narrow human experience, using a little common sense, and perhaps even some informed intuition, with the intention of obtaining insight by the most honest means in my possession. Each day I am reminded of Friedrich Nietzsche’s words, which should precede every scientific inquiry and should be included in the intellectual gospel of every honest human: “Convictions are more dangerous enemies of truth than lies.” When observing the natural world, our mission should be to approach any ecology or any organism without preconceptions and, more important, abandon that imperial sense of human superiority, which always suggests that we know something even when we clearly do not. A position of superiority always provides the worst possible perspective and is anathema to any clean and honest observation—whether scientific or not. The objective should be to metaphorically approach any phenomenon of the natural world with your hat in your hand. I find humility to be increasingly easy to come by after so many years immersed in the lives of other creatures. Like a great enigmatic onion, complexity increases as we peel away successive layers of the underlying mysteries that always characterize the natural world. Get down, get your nose on the ground merely following your common senses, get out of your own way, and simply pay attention.

Author in summer on 12,200-foot Middle Mountain. Photo by Dawson Dunning.

With this approach, it is possible to ask the fundamental questions—who are the personalities and what are those extraordinary characteristics and capabilities that define the species? I have always not merely observed but developed relationships with other creatures, and, occasionally, through our common bonds of trust, tolerance, perhaps mutual interest, or—even on occasion—shared affection, we have come to know one another. I am convinced that only through the possibilities

provided by this level of interaction may an animal gradually begin to fully reveal itself.

Big Horn Sheep on Middle Mountain. Photo by Dawson Dunning.

Ethology is simply an effort to observe any wild creature under the most natural circumstances possible—preferably with no captivity, no cages, no restraints, and, presumably, little interference or disruption created by the observer. One option may involve observing at a distance with a good pair of binoculars, a camera, and a notebook, as some extraordinary organism goes about its life in its otherwise ordinary way. Or, as I prefer, the observer may choose to gain a more personal and rigorous perspective of the individual or group of individuals being studied. Obviously this approach dictates a necessity of encountering more logistic difficulties and investing more time on a more persistent basis to create a level of comfort in a creature ordinarily unaccustomed to the company of a nosy human. This is often referred to as the process of habituation—you become such a common feature within another animal’s landscape that you are eventually proven to be at least reasonably safe. Then, when the subjects of your relentless investigation become so bored with your presence, you may be ignored entirely.

In time you may find yourself immersed in the fascinating life of another animal, and, perhaps more remarkable, you find that another animal has permeated your life with the richness of its own. The animal has generously contributed to your life in ways you could never have foreseen. And do not fear or flatter yourself with the suggestion that your presence is likely to alter a wild creature’s fundamental nature, for most animals in their natural setting are far more willful and headstrong in the way they express their innate behavior than you or I tend to be. If you find yourself embedded in the society of another creature, in all probability, the only behavioral changes that are going to occur will be your own. Predictably, you will be the one whose fundamental nature has been altered in surprising ways.

Touching the Wild

Touching the Wild