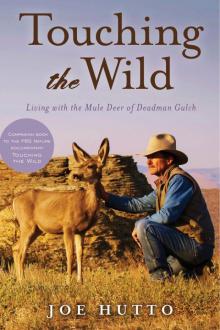

Touching the Wild Read online

Page 4

Another doe in the group that immediately captivated our attention was Notcha—a profoundly beautiful and elegant deer without a surviving fawn that year, but with a distinct notch taken out of her left ear. She seemed captivated by our attentions and had a particular affinity for Leslye. Another deer with a large, crescent-moon-shaped scar on her shoulder we came to know as Crescent. She had fawns that year whom we named New Moon and Luna; however, Luna eventually became Luno when his gender was finally revealed.

In late November, we began to observe our first rut at the Slingshot. At this time, mule deer bucks, like male animals everywhere, become distracted and obsessed to the exclusion of either food or rest. A large, beautiful buck we called Daddy Buck, joined our herd of twenty-five does and fawns, and although the occasional contender would wander by, this dominant buck’s authority was rarely challenged. He was easy to recognize, not only because of unusually large antlers supported by a massive, swollen neck, but also because the antlers were “nontypical,” with a rather gnarly configuration that lacked symmetry and with a smattering of extra small tines here and there.

Notcha.

Rutting mule deer bucks, although profoundly wary most of the year, can become almost oblivious to humans when preoccupied with prospective mates. If you are standing twenty feet from twenty does and fawns in the first week of December, the biggest buck may pass by close enough to touch you, offering only a nervous glance and a canted ear that dismisses your odd and inconvenient presence.

Daddy Buck immediately identified us as safe neighbors and in a few days became entirely comfortable with our presence. Dominant bucks normally lack the nervous insecurity that the younger two- and three-year-old bucks display around the herd. These older mule deer bucks, by comparison, seem to remain composed and rather dignified, having earned a secure standing among other deer. They can be surprisingly polite, merely making themselves available to a flirtatious doe while remaining highly conspicuous to other optimistic bucks, whereas younger bucks can be terribly annoying to does nearing estrus. Dominant bucks are also gentle and indulgent with the fawns and will even allow the little ones to share food, eating nose to nose. Buck fawns display a cautious but almost obsessive curiosity with the great bucks; they are allowed to sniff around the head and antlers as if they may be anticipating the possibility of one day also becoming such an imposing presence. In contrast, these behaviors would be considered horribly rude by most does, and would invite a brisk hoof laid squarely between the thoughtless fawn’s ears.

A doe in heat may be attended by the dominant buck for twenty-four hours or until she has completed her cycle. During this season, bucks eventually become starved and exhausted, so Daddy Buck would lie and sleep for hours during midday—and was obviously grateful for some high-protein supplemental food that we would offer him on occasion.

Moses, a gentle giant.

Notcha with Moses.

Daddy Buck was in attendance for two years before he was displaced, but he was with us only during the rut—then he would mysteriously disappear for the duration of the year. We saw him pass by the third year, but he politely surrendered the area to a more dominant and imposing buck we named Moses. When three-hundred-pound Moses swaggered into the yard with head lowered and ears canted back, we were reminded of the Red Sea parting, as thirty-five deer respectfully moved far to either side.

The first year was our introduction to this herd of deer that would eventually capture my attention and curiosity in ways that I had never imagined. Each year has been an exercise in uncovering successive layers of complexity that define the life of the mule deer and their extraordinary relationship to this diverse landscape. However, this was the beginning that would later offer possibilities that any scientist or ardent observer would find irresistible. Socrates said, “The unexamined life is not worth living.” I would agree but further amend that by saying that, for some, it is the examination of other living things that makes life worth living.

C H A P T E R T H R E E

An Inflorescence of Mule Deer

Even on a small ranch like ours, life can be consumed by the constant attention required of horses, fencing repairs, irrigating, growing and harvesting hay, and keeping noxious weeds at bay. Each summer our dear friends Jack and Robin Malmberg, with daughter Ingre, bring three teams of great draft horses, along with the appropriate one-hundred-year-old, steel-wheeled McCormick mowers, and spend a week cutting and baling our hay. It’s a hard-working but delightful time, tending the land in a traditional way with the gentle giants that quietly and steadily pull us all along. The deer had migrated in May to their summer range, and we had no communication with them until summer came to an end, when we were delighted to see familiar deer faces returning. Last year’s fawns were almost grown and independent but still entirely recognizable. And of course the familiar does from the previous years were returning and introducing us to their new fawns. These deer that we had known from the previous year, although somewhat nervous from being out of human company for six months, quickly recognized us and within hours were again familiar and comfortable to be within a few meters of us. Clearly, the new fawns judged from their mother’s demeanor that even though we were a strange curiosity, we must be a relatively safe curiosity. Their behavior was distinctly different from the fawns we had met the previous year. In fact, the new, wide-eyed fawns were so accepting of us that it was hard to avoid the improbable suspicion that they had received some prior instruction on what to expect. Even the yearling fawns from the previous year were decidedly more comfortable with our proximity than they had been when last we saw them—as though they had forgotten the exact previous spatial boundaries that we may have shared in those months last winter, and now these new boundaries were less rigidly defined.

Jack, Robin, and Ingre Malmberg cutting hay with 100-year old horse-drawn mowers pulled by their Belgians.

After many weeks, we sadly concluded that Rayme had not survived the summer or perhaps the migratory gauntlet back to her home winter range. I still regret not getting to know her better, for clearly she was extraordinary. She had bridged the divide between her family and ours, and all that has transpired is her lasting legacy. Rayme was something of an oracle who voluntarily brought a message that merged one universe with another—she was the one who so generously and unexpectedly chose to share her unique vision of the world. Rayme opened a door I never knew existed.

As the season progressed, the deer began returning in waves that would include four or five at a time. One cool October morning after a light snowfall, I was standing in the yard scattering some alfalfa hay, surrounded by a few deer, when I saw several other deer coming down through the sage brush from the mountain behind the house. Leslye had been particularly anxious, waiting for Notcha’s return, but so far there had been no sign of her favorite deer. That morning, as Leslye stood in the window, I pointed to the arriving deer and suggested in some sort of sign language that one of the deer coming might be Notcha because of a left ear with a visible notch. I pointed, and Leslye nodded with a big grin. The gorgeous and distinctive deer entering the yard could only have been Notcha. But the new arrivals saw me and immediately stopped and became noticeably nervous. All five deer suddenly turned in fear and began trotting back out of the yard toward the mountain. Leslye exclaimed through the glass, “Say her name! Quick!” I called in a loud voice, “Notcha!” Then I repeated, “Notcha!” To our absolute astonishment, Notcha stopped and turned, staring momentarily, and, then, leaving the other deer, ran—yes, ran—at a gallop directly to me. We were stunned at the revelation that she not only recognized my voice and knew exactly who I was after six months without doubt, but, even more amazing, recognized her name! Following Notcha’s example, the other deer soon joined us for a few minutes of casual greetings that included a few horse cookies. I returned to the house astonished. Why on earth would a wild deer have the capacity to so readily recognize and retain the oral association of some name that had been arbitrarily assig

ned to her in a previous year? I began to wonder how that particular kind of identification could be included in the deer’s repertoire of social possibilities—and why. It was at that moment that I began asking a question that still haunts me: “Who am I am actually dealing with here, and what are the possibilities?”

Frosty, who had been a bit of a runt as a fawn, shown here well developed at three and a half years old.

With the exception of Rayme, all the deer seemed to have eventually returned, including Raggedy Anne with her new fawn, Mandy, plus the older twins, Rag Tag and Frosty, and Anne’s oldest daughter, Charm. Anne’s maternal herd seemed to be complete. Charm had arrived with an adorable waif of a fawn at her side, who had small, delicate features that brought the name Possum to mind. With a little, pointed, gray face and penetrating, jet-black eyes, the cute baby possum reference was almost unavoidable. Little Possum was immediately engaging and seemed to have a particular enthusiastic fascination with us. Within a week of our introduction, we found that Possum could not stay out of our pockets. While we did not think to reach out and touch the deer in our first winter with them, Possum invited us to breech the divide of physical contact. We found other deer, including Notcha, who seemed to enjoy the contact and sought it out.

The mule deer coat, or “pelage,” is composed of uncommonly dense, heavy, coarse, hollow guard hair with a soft, almost downy, undercoat. On below-zero Fahrenheit days following relatively high humidity, these deer occasionally become completely enshrouded in hoar frost, a feathery, white covering of ice crystals. On cold, gray days without the advantage of direct sunlight, this frosting may remain with no inclination to melt, but the deer, having impeccable insulation, remains warm. On extremely rare occasions in spring, a cold, freezing rain can saturate the deer’s coat, and a deer may shiver. A little direct sunlight, however, is an immediate remedy. People who study solar energy should take careful heed of the mule deer’s remarkable hair. The moment the pale rising sunlight hits the mule deer’s coat, even on the most brutally cold mornings, the hair suddenly spikes in temperature, feeling impossibly warm to the touch. Their coat has a remarkable ability to absorb and capture the sun’s radiant heat with extraordinary efficiency. Many winter mornings while out browsing at daylight with the deer, my gloves will fail me as my hands begin to ache with cold. Quickly, I find an accommodating deer, remove my gloves, and bury my hands in its warm coat as it continues browsing along. In a minute, my hands are recovered enough to reenter my gloves, which have been warming inside my coat.

Another deer had returned from the previous year whom we had known and thoughtlessly assigned the unfortunate name Rodenta, because she and her apparent sister Dauby were both a bit—well—rat-faced. Now we saw Rodenta as a strangely beautiful doe with a distinctive Roman nose and exotic, almond-shaped eyes. Dauby, on the other hand, was always pitifully shy, with droopy, sad-sack ears, and invariably brought to mind Dobby the house elf from the Harry Potter stories. Several new faces arrived that fall but were undoubtedly members of the same local winter herd that had finally been convinced to enter the yard of our house. Crescent was again with us and in the company of a new fawn whom we named Retta, in reference to fawn spots that were retained in a reticulated pattern down both sides of her back. All of Crescent’s subsequent fawns have displayed this peculiarity.

Charm at the gate.

A young, insecure buck, whom we had known only as a shy and reclusive fawn from the previous year, also arrived that fall with his first set of antlers. And, as young, insecure bucks are prone to do, he could be a bit of a bully around the does and fawns. He had an unrefined head and a somewhat coarse facial appearance, and because of his rather bad attitude, we named him Stinky.

We quickly recognized that there was something special about Raggedy Anne. In the midst of constant minor mule deer bickering and rancor concerning issues of status and hierarchy achieved through expressions of dominance or submission, we noticed that Anne was never the focus of these disputes, nor was she ever inclined to express any superiority toward any other deer. Gradually, as we came to recognize some of the more subtle communication that was unfolding around us, we observed, for example, that when Anne’s space was being violated, she would simply look and raise her chin, and, without fail, the offending deer would acquiesce, moving away with barely a glance. It was clear that Anne was the dominant doe, the mild-mannered matriarch, a most humble queen, and for our first season with the deer, we had never known this to be the case. Anne was treated with deference by all the other deer. With no need to reinforce her position of authority, she seemed almost passive and disconnected from the busy social activities around her. All does defer to all antlered bucks, but, still, throughout the winter months, the related bucks are inclined to follow the maternal herds. However, we always noticed that when the deer were on the move, it was usually Anne who would first begin walking away from the group with her immediate family in tow, and, then, the other deer—bucks included—would tag along soon after.

Raggedy Anne—the face of a veteran.

When we first met Anne, she was a fully wild deer who was obviously unfamiliar with humans and was slow to be fully trusting, but in her third winter with us, she suddenly had a change of heart. Many deer who are initially uncomfortable and suspicious may eventually lay their apprehensions aside with an expression that looks and feels more like a surrender than a mere compromise involving possible conditions. Suddenly, one day, a deer who was previously fearful may in a single moment walk forward in an ordinary manner and take a cookie from your hand. It sometimes feels as if the deer has shrugged off its apprehensions in one single, conscious declaration of faith. In one gesture, you see a historically wide, fearful eye soften, and with no further trepidation, a deer will walk up and stand by your side. I witnessed this transition over and over again. It is as if these deer have a rigid, biologically defined flight distance of about ten or fifteen feet that, when maintained, allows a possible escape from an attack. But, surprisingly, once the deer allow themselves inside that zone, rather than becoming overwhelmed with anxiety, they instead seem relieved of the instinctive obligation to maintain the flight option. It seems as though the flight switch is suddenly flipped into the “trust” position. I have at last proven to the deer, and they are at last satisfied, that I can be trusted. There are, of course, some deer that even after many years will approach for contact but are always wary and uncomfortable.

One day in early fall, in this way, Anne declared that she could trust me with her life: her eyes went completely soft, her ears dropped slightly, and with a brisk, momentary flick of the tail, all fear seemed to vanish as she approached with no apprehension. This was clearly not the result of gradual habituation but a sudden and conscious revelation based on my persistence in never doing her harm. If there was habituation involved, it was entirely my own. Thereafter she never hesitated to approach for a treat or even to be stroked, and she enjoyed a light scratching along the sides of her neck. And as if exercising some sort of discrete etiquette, she would ever-so-gently grasp a cookie with her warm, soft mouth and wait for my release. Then, while chewing, in a gesture of complete trust, she would look away into the distance, canting her ears and her attention toward the far side of the canyon—still maintaining her eternal vigil for any possible danger—but a vigil that no longer included me in her universe of possible threats. Winning Raggedy Anne’s trust and confidence—winning her heart—was one of the great rewards of my life and hinted at the many possibilities that still waited to be revealed.

Rag Tag.

Late one afternoon, following time spent in close proximity involving a few treats and grooming with Raggedy Anne and her family, Leslye and I eventually walked into the house and made eye contact; Leslye slowly shook her head and said with a tone of near disbelief and wonder, “What a gift.”

Within days of Anne’s acceptance, her fawns made similar concessions. Frosty would cautiously approach to take a treat, but Rag Tag essentiall

y shrugged one day and came marching up to retrieve multiple cookies, as if she had been doing this all her life. Rag Tag was also a “breakthrough” deer in that she was not only one of the first to enjoy being scratched and groomed but the first to begin returning the favor. As I scratched her neck, she would bend around, alternately licking and nibbling on my coat or occasionally grooming my hair and face. Mutual grooming is an important aspect of mule deer social interaction and bonding within the herd. A mule deer will not engage in mutual grooming with just any other individual deer, but rather will do so only with family members or the closest of affiliates. Rag Tag was clearly conceding that I was a member of her most immediate family.

Our second winter season on the Slingshot Ranch was filled with new discoveries about the local landscape generally, and, in particular, we began to discover secrets about the more personal and individual landscape of the mule deer. Although we were saddened to learn that Rayme would not be joining us for a second season, we were heartened to reacquaint with deer from the previous year and begin meeting numerous new and often surprising arrivals throughout the fall and early winter. One day we quickly observed two new standouts in the crowd as a distinctive pair of twin yearling does took up residence with the local herd. These were yearlings—fawns from the previous year who were around eighteen months old. We noticed that they were obviously separated from their mother, but judging by their relative physical condition, these two had been well cared for as younger fawns. Also, they were clearly accepted among the herd at large, suggesting that their mother had close affiliations with these deer, although there was no question that these two had not been with us the previous winter, for their appearances were so distinctive. There could be little doubt that even after six months we would have still recognized them immediately. The two young does were strikingly marked with shades nearing pure black and pure white, and a skunk analogy quickly came to mind when looking at their beautiful but unusual faces. With the margins of their ears lined in black, and the interior virtually stuffed with snow white hair, both yearlings also sported blackish crowns and pale eye rings, so it was only after a few weeks that we stopped referring to them as “the skunky girls.” Soon we began to know one as Cappy—because of a perfectly delineated and uniformly black forehead and crown like a sailor’s watch cap—and the other as Flower—yes, a shameless reference to Bambi’s skunk friend.

Touching the Wild

Touching the Wild